What is Heuristic Decision Making?

Heuristics is originally a Greek word that means to find. Heuristics are unconscious ways that we process information more quickly than if we were to think about it consciously. The brain takes mental shortcuts to save time by thinking logically about things. There are many different ways (cognitive biases) that our brains have developed during the history of mankind to manage information in a faster way than rational thinking. The vast majority of our daily decisions are taken up by heuristic decision making.

Landing Pages

Just like the aforementioned legal contracts, sales pages are often very long and contain a variety of elements whose purpose is to convince us to buy the product by appealing to our heuristic decision making.

Length and Volume

The reason that sales pages are often very long and contain a lot of material–such as information in bullet form, pictures and lots of recommendations of satisfied customers–is in the hopes that you, as a consumer, will think: “Ah, if this much is written about the product, and if this many people (experts) recommend the product, then it must be good.” Of course this doesn’t work with all consumers, and there is no completely superior outline for how the optimal landing page should look, but it’s obvious that this longer version works well. Otherwise, it wouldn’t be used so frequently. Ultimately, length or volume are not indicators of the quality of the information, but it’s easy for us to get automatically tricked by our heuristic decision making to believe just that. It’s not that our brains are evil and are trying to fool us, but simply that they make this tradeoff of accuracy to save time.

Nazi Germany

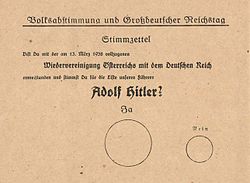

Heuristic decision making has always been an important part of politics and throughout history, there have been many tricks to convince the crowds. Various means of manipulating the media have existed for as long as civilization has existed. A less known part of the Nazi Party propaganda strategy was in the design of the vote ballots for the Austrian union with Germany in 1938. The circle to vote “YES” was considerably larger than the circle to vote “NO“. Due to its size, we unconsciously attribute more importance to the bigger circle and are more drawn towards it. An overwhelming majority of the Austrian population voted for the reunification with Germany.

Speeches and Presentations

Just like the example with the landing pages, we are often influenced by the length of the speech or the reputation of the speaker. These things really have nothing to do with the content, yet through heuristic decision making, we think they do. Suppose you are sitting in a meeting and listening to a speaker who talks about a topic that you know nothing about. Even if the speaker doesn’t really say anything particularly clever, after a while, you will start to have a certain amount of confidence in him given that you do not know anything about the subject. Just the fact that the speaker is able to talk about something in a certain amount of time (say 20 minutes) in a coherent manner gets your heuristic decision making to conclude that the speaker probably actually does know what he’s talking about, and that the content probably actually is clever, though perhaps you cannot understand its meaning. Furthermore, if the speech was really as bad as you suspected at first, wouldn’t you have just left? In both of the above cases you are post-rationalizing to find a reasonable explanation for what is happening right now. Another way of putting it is that your brain is trying very hard to avoid cognitive dissonance. In the first case you rationalize the situation by thinking: “Well, if this guy who is speaking can go on for 20 minutes he probably knows what he is speaking about, even if I don’t.” And in the second case you are likely rationalize by means of wanting to keep your self-image intact: “I wouldn’t listen to bad speeches or waste my time with stupid people, that’s not who I am. Therefore the fact that I have sat here for a long amount of time has to mean that this speech is good. Otherwise I would have left–wouldn’t I?” In both of these cases, your brain is trying to piece together the reality of the current situation by means of explaining the past in a not so accurate manner. In this second case, maybe you even begin to perceive the speaker as an expert in his field, which brings us to the next example.

Authorities and Experts

It is a well-known fact that we often rely on experts’ or authorities’ opinions instead of thinking for ourselves. It is not a coincidence that Nike sponsors Tiger Woods or that a stock plummets when its management and other insiders inexplicably sell their own shares. Nor is it a coincidence that people in the financial industry dress very nicely and talk in terms that are difficult for a lot of ordinary people to understand. This is done deliberately to be perceived as experts. If the average person knew that most financial advisors are actually glorified salespeople that rarely beat the index and usually just place your money in an index fund and takes a percentage cut for it, they would not choose to invest their money with them.

Computer Programs and the Internet

How often do you actually review the terms of a downloaded computer program, a phone app, or some Internet service? Probably not very often. You just want the program to work immediately and you feel that you cannot be bothered reading through the fine print: whether the program gets access to your personal information or is allowed to monitor your web behavior only plays a minor role in your decision–you don’t have time or energy to think about that. Maybe you’ve checked one of those boxes where you, without thinking about it, have relinquished ownership of your soul to the creator of the computer program.

Conclusion

We are getting bombarded with more information, choices, and offers than ever before in history, and it’s unlikely that this trend is going to slow down in the future.

At the same time we are becoming increasingly specialized, and specialization comes at a price–we have to spend our time and energy on only a few areas of knowledge. This forces us to trust in specialists of other areas instead of learning these things for ourselves.

This is a good thing viewed from a global market perspective, but it is very harmful to the single individual because he will not be bothered to make fully informed decisions.

We don’t have the time to evaluate all alternative in today’s information society. This means that we are less likely to increasingly rely on heuristic decision making to save time.

What role do you think that heuristic decision making will play in the future of mankind?

Will its use increase or decrease?